The Liturgy of the Palms

Luke

19:28-40

Luke

19:28-40Psalm 118:1-2, 19-29

The Liturgy of the Word

Isaiah 50:4-9a

Psalm 31:9-16

Philippians 2:5-11

Luke 22:14-23:56

I don’t know about you, but I have

questions about the stories we just heard.

I have questions about Jesus riding into Jerusalem and the crowd that

waved their branches and laid their cloaks down in the road ahead of him, shouting

“Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord!” And I have questions about the other story,

the one about the crowd that dragged him before Pontius Pilate shouting

“Crucify him! Crucify him!” I don’t know what Jesus was expecting to

happen after coming into Jerusalem like that.

If we can believe the gospel accounts, he knew things were going to play

out just the way they did. But, if he

knew he was going to be killed, why did he go?

The centuries have produced a

variety of answers to that question.

Mostly they are theological interpretations of his death. Jesus went to Jerusalem, the theologians

say, in order to die. And they offer

explanations of what it was that his death accomplished, and why it was only in

dying that he could finish the work God sent him to do. These

theories of The Atonement—about how Jesus paid the penalty for our sin, or how

in dying he overthrew the powers of death, or how he gave for all time a perfect

example of self-sacrificing love—these theories are meant as answers, but they

only raise more questions— important questions, worthy of careful study and

reflection, but that can also seem kind of remote from you and me and the

decisions that we have to make every day about how to live our lives.

But there is something about the

way we tell the stories this morning, how we act them out, or put them on, if

you will, that suggests that they are meant to relate to us. They ask questions that we are supposed to

answer. And some of these questions are

hard. But I think that on the human and

historical level that’s what Jesus rode into Jerusalem to do—to ask hard

questions. The first thing he does when

he gets there is to go into the temple and make a scene, driving out those who are

selling there, and calling the place a “den of robbers.” It is a confrontation, the action of someone

who means to be reckoned with. But it is

not the first strike in a battle to take control; it is the opening statement

in a conversation. Jesus isn’t there to

fight, he’s there to talk, and it seems like what he most wants to talk about is

the temple, and the people who are in charge of it.

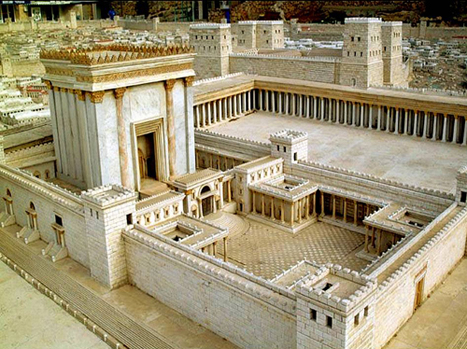

The temple in Jerusalem was like

the Vatican, Washington, D.C., and the New York Stock Exchange all rolled into

one. It was the institution that

dominated Jesus’ world, the center around which the political, economic,

social, and religious map of the life of every Jew was drawn. And as Jesus went around in Galilee, driving

out evil spirits, healing the sick, preaching good news to the poor,

ministering with compassion to people who were like sheep without a shepherd, he

ran into the local representatives of the temple. They challenged his authority to do the

things he did and they questioned the way that he did them. And he confronted them about their hypocrisy,

and their failure to practice what they preached, and challenged them to renew

the essential spirit of their religion. But

this conflict was a stalemate, and it only intensified, until it was inevitable

that Jesus would carry the argument to its source.

Jesus didn’t go to the temple to

seize power—he went there to talk. But

he wanted to talk about the things that the elite at the temple didn’t want to

talk about. It’s true that they came to

him with questions, which he answered with questions of his own, and after one

or two of Jesus’ questions they shut their mouths and went away. And that was because they weren’t really

interested in dialogue. When the chief priests

and the scribes sent their spies, as he is teaching in the temple, to ask him

“Is it lawful for us to give tribute to Caesar, or not?” they weren’t actually

interested in having a conversation about the economic arrangements in an

imperialistic world system. They weren’t

asking to talk about the relation between the sovereignty of the Emperor and

the sovereignty of God, and which is more deserving of our allegiance. They were simply bandying words, trying to get

him to incriminate himself, and when he tried to lead them into a real

exploration of the truth, they had nothing to say.

By the time that Jesus was standing

before the high priest himself, he had nothing more to say, either, because it was

clear by then that there was no hope of having a real conversation. Maybe the gospel writers are right, and he

knew all along that this was how things were going to go. Maybe he had no expectation that the temple

elite were going to listen to what he had to say. Maybe he knew perfectly well that they would

never open their lives, to an honest examination, let alone consider going in a

different direction. But that’s the

thing about knowing the truth—about being committed to the God whose Spirit is

truth. You can’t just sit idly by while

the nation you love is poisoned with a never-ending diet of lies. You have to speak up; you have to ask

questions about what is really going on.

On this Passion Sunday, Jesus

challenges us again to make our churches places where the hard questions are

asked, and where real conversations can happen. It’s interesting how many of the gospel

stories about Jesus’ arguments with his enemies take place while he is

worshipping with them in the synagogue, or in their houses having dinner. If Christian churches can’t hold open a space

where people can talk about the hard questions without the stridency of entrenched

ideological positions, where else will we find that space? Can this church be a place where we talk to

each other about the things that matter without asking ourselves “is this

person a Liberal or a Conservative?” but rather, “What are her values and

concerns? What beliefs and experiences

have shaped her understanding of the world?

What can she teach me?”

Jesus rode to certain death because

he trusted that love is the truth, and truth only becomes truth when it is

communicated. The truth is something

that lives between us, in the space where we touch each other. Jesus learned about this from God, and so he

trusted that God would use him for the truth, even if the only way he could tell

it was to die. So one of the benefits of

his death and passion is that we, too, can risk the truth. We can venture into the space between us

where no one is completely guilty, because no one is entirely innocent. We can sustain a conversation about the hard

questions, because Jesus showed us that if we can’t talk honestly about power,

our justice is a lie, and if we can’t talk openly about war, our peace is a lie,

and if we are afraid to talk about evil, our goodness is a lie.

And to live a lie is to die every

day, a slow, painful, meaningless death.

But as he is dying, Jesus

turns to the repentant thief, the one who in the agony of crucifixion finally

admits the truth about himself, and he says “today you will be with me in

Paradise.”