A

few weeks ago, the church Stewardship Committee drafted a cover letter for the

forms we pass around every year at this time, so that people who wish to can go

on record about how much they hope to give to the church in the coming year, in

time, and talent, and money. And every

year, because this letter goes out in the name, not only of the Stewardship

Committee, but also of the vestry (which board of directors), a draft goes to

the vestry for review. In the past, the

vestry has typically given the letter a quick once-over, and said, in essence,

“looks fine to us—where do we sign?” But

this year was different. Maybe it was

because the letter talked about making changes to the Stewardship program in

order to deepen the conversation, but in any case, this year your vestry took a

hard look at it. They made editorial

suggestions to clarify its message, but more than that they raised substantive concerns

about its contents, and questioned some of its basic assumptions.

The vestry’s

comments were mainly concentrated on those parts of the letter that talked

about giving money to the church in proportion to one’s income, and in

particular the traditional norm of the tithe, that is, of giving one-tenth of

it. Now tithing is a biblical standard, with

a solid weight of church behind it, so I was a little surprised at first when

the vestry called it into question. After

all, the Stewardship Committee’s language in the letter about these things had

been simply carried forward from last year’s letter, and last year’s from the

year before, and no one raised an eyebrow about it then. But, of course, maybe that’s just because no

one was paying attention.

However,

one of the things that I value most about this congregation is that its’

members do notice, sooner or later, when we are doing things that don’t sit

exactly right with them, even things that are “traditional,” and they aren’t

afraid to question them. And the truth

is, we haven’t really taken the time before now in the vestry, or even in the

stewardship committee, let alone the wider congregation, to look at why and

whether tithing really is an expectation we have of ourselves and one

another. So I took the discussion about

it in the vestry meeting as a sign that the Stewardship Committee is on the

right track in saying it is time for us to open this topic up for a deeper

conversation, and as a promising start in that direction.

The

most telling moment in the discussion, for me personally, came when someone

said, and I’m paraphrasing here, “I don’t tithe, so how can I tell the congregation

that this is something they should be doing?”

Which would have been the perfect opportunity for me to lead by example,

and to take a stand for the traditional norm, by saying, “well, I do.” Except the truth is that I don’t. Most of the time I feel guilty about this,

like it makes me, on one level, a fraud, who is shirking his ordination vow to

“pattern your life and that of your household in accordance with the teachings

of Christ, so that you may be a wholesome example to your people.” Somehow, though, when that vestry member

spoke out in such a forthright way, I felt relieved. I was even thankful that I have, as yet,

failed to meet the standard of the tithe, because if I hadn’t I would have been

sorely tempted in that moment to say so.

And there would have no way to do that without putting others in their

place. As it was, I had no leg of moral

superiority to stand on.

I do

know people, even some in this congregation, who can speak quite movingly about

how committing to the tithe has helped them to grow spiritually. But none of them talks about their

satisfaction in setting a good example for others. Nor do they mention a feeling of relief at

having rid themselves of the guilt of not tithing. They are more likely to talk about

discovering a freedom and joy in giving that makes them want to do more. And when you think about it, there is

something arbitrary about the tithe--if the idea is to honor God and

acknowledge our dependence on God’s providential goodness, why stop at ten

percent? It’s a norm that comes from the

Jewish law, and without negating it, Jesus sets quite a different standard. You can find it in the 18th

Chapter of the Gospel of Luke, a few verses after today’s reading: “One thing

you still lack. Sell all that you have

and distribute to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven.”

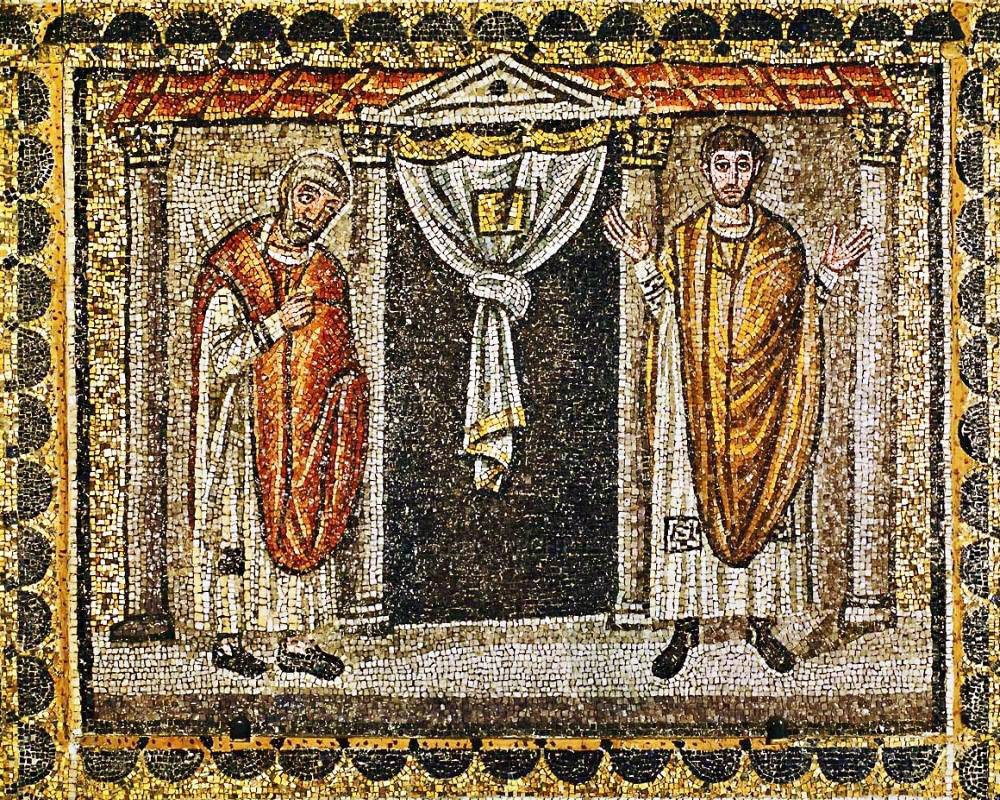

There’s

nothing in the Gospels to suggest that Jesus was against tithing, but teachings

like the story of the Pharisee and the tax collector warn against thinking that

tithing or not tithing makes a difference to God. Jesus seems to assume that most of his

audience don’t, or why else would the Pharisee imagine that his tithing sets

him apart from other people? Of course

the tax collector thinks of himself as set apart also, for a different

reason. People despised tax collectors

as treacherous and wicked because they collaborated with the pagan and

idolatrous Roman overlords. And for a

person with a sensitive conscience that must have been a heavy burden to

bear. No doubt that is why this man is

beating his breast and crying out “Lord, have mercy on me a sinner.” But Jesus seems to think that this is an

appropriate way of relating to God, not just for tax collectors, who were

generally landless people, just doing what they had to do to survive, but for

all of us—“Lord, have mercy on me a sinner.”

We

modern liberal Christians are wary of such lavish expressions of guilt and

repentance, which we associate with an oppressive religion that is, thankfully,

out of date. And it is true that the

church has used guilt to terrible effect, causing untold harm to countless

persons. But that is because its

teaching has often implied, whether openly or not, that there are some people

who are not guilty, saints or pastors

or priests or popes who have made the grade with God and now stand in moral

superiority over the rest of us.

But if

you look at the moral standards Jesus sets, they are so high that only God can

meet them, and this has the effect of showing that we are all guilty. Consequently, no

one is in a position to condemn. Any money we have is dirty money, as

long as there are people who have none, and the tax-collector in the story is

far more ready to admit this than the Pharisee.

Which makes him the kind of person God can work with, a potential member

of the new, redeemed community that Christ is bringing to birth.

I

think that Jesus has that community in mind when he comments at the end of his

story--“for all who exalt themselves will be humbled, but all who humble

themselves will be exalted." To me,

this is not a description of a system of rewards and punishments, but of what

it will realistically take to arrive at a community where there are no longer

superiors and inferiors, but where we can all look each other in the eye. And the allure of that community is enough to

exert a draw even on a greedy, bewildered, and cowardly person like me.

For

that reason, I value the tithe as a personal guidepost. Jesus’ advice to sell all I have and

distribute to the poor seems impossibly remote from where I currently stand,

sinner that I am. But giving away ten

percent is a goal that is, at least imaginably, within range. It is close enough to exert a gravitational

pull on my generosity, stretching me to give a little more every year, not only

to the church, but to other organizations that also do the work of exalting the

humble. I say this as someone who lives

in security and comfort, in no danger of going without the necessities of life,

at least for now. What Jesus reminds me is

that this is not a condition that I, any more than the poorest person in the

world, can claim to deserve.