The question about what happened to

the body of Jesus in the early dawn of that Sunday morning is not the essential

Easter question. The most important

thing about the resurrection isn’t that something happened to Jesus. It is that something happened to us.

Strictly speaking, we can’t really know what that something is, because the

resurrection is a process that is still ongoing. The Letter to the Colossians is very clear on

that point, when it says, “your life is hidden with Christ in God. When Christ

who is your life is revealed, then you also will be revealed with him in

glory.”

This is what Mary Magdalene and the

other Mary found out when they went to the tomb that morning. They went there full of grief, still reeling

from the shock, trying to make sense of what had happened to Jesus. They went to mourn and to cherish the memory

of what had been lost, and they found something, something new, that now

belonged to them. They went to the tomb

to say goodbye to the past and they came away as bearers of a message about the

present and the future--a present and a future with Jesus.

Still, there is no getting around

the fact that this message came to them at the tomb. Resurrection gives new life and meaning to

the story of Jesus, but it is still the same story that came to a head at the

cross. Easter does not reverse Good

Friday. But Good Friday and Easter

together confirm what the story of Jesus is all about. You could boil it down to a couple of points,

and they were exactly the points that Jesus kept trying to make, and they were

what got him into all that trouble. The

first one got him into trouble with his disciples, and I suppose it still does,

and that was the point that his mission really wasn’t about him. It wasn’t about his charisma, or his

remarkable abilities, or his chances for success. Jesus lived and died for us, for our repentance, our instruction and empowerment, our

forgiveness, and healing, and liberation.

The second point got Jesus into

trouble with the religious leaders and political authorities, and it also still

gives a lot of people problems. And it

was that the author of his life, the power behind his deeds, the source of his

wisdom, and the driver of his mission was God.

It was God who sent Jesus on the road that led him to the cross, though

it was not God who killed him. And it

was God who raised him from the dead—so there could be no doubt who was

responsible for the sending, and who did the killing.

The church, then and now, is the

community that gathers to experience the death and resurrection of Jesus as a

present spiritual reality. This Spirit

tells us that Jesus did what he did by the anointing of God, and he did it to

show us how to live together in peace and forgiveness and love. And the very first Christian communities came

up with a shorthand, a phrase that encapsulates all of this, which is simply, “Jesus

is Lord.” The essential question about

the resurrection is not, what happened to the body in the tomb? It is, “do you accept that Jesus is Lord?”

Now before you go rushing to answer

that question one way or another, let me state very clearly, just so nobody

gets the wrong idea about me, or about this church, that any answer to that

question is permitted here. Seriously—I

mean that. And let me also say that I

think that the acceptance that this question asks about is like the

resurrection itself. It’s not a box you

check, and then move on to the line about your address and credit card

number. It’s a process. We’ve only begun to glimpse what it would mean to fully accept

the Lordship of Jesus, which is to say, the total transformation of the world

into the paradise of God.

But back to the story: the

resurrection proves that Jesus was telling the truth about himself, even though

nobody believed him. Well, almost nobody. Mary Magdalene and the other Mary believed,

at least enough to risk sticking around to watch his crucifixion. They believed enough to want to go to his

tomb and pay their final respects. I

guess that is what made it possible for them to witness his resurrection, and

to receive the message that the work that God is doing through Jesus is just

getting started.

But the male disciples, according

to Mark and Matthew, aren’t ready yet.

Their hearts are still too clouded with guilt and fear; their heads are

still too full of the splintered wreckage of the grandiose dreams that they

brought with them to Jerusalem. They will see Jesus. They will experience his resurrection. But not until they follow him back to

Galilee. They have to go back, back to

the beginning, back to the place where he first came upon them, casting their

nets into the lake. Not to try to

recapture the past. Not to go on some

kind of nostalgia trip, but to hear again in the present the voice of Jesus

saying “follow me.” They have to go

back, carrying with them the memory of his death, and their part in it, and begin

again to learn how to be his disciples.

26 years ago I spent a couple of

months in Nicaragua, building houses and seeing for myself what the

counterrevolutionary war was doing to that country. A lot of wonderful things happened to me

there, and most of all I fell in love with the people. And while I was there I met a young American,

a mechanical engineer, who was machining parts and fixing up old 1930s

windmills around the country to help the farmers pump water. And maybe it was he who gave me this mild

case of the romance of revolution, and I started to imagine learning about

organic agriculture and going back to Nicaragua or some other down-trodden tropical

country to help the people.

But on my way back to the States I

came through customs in the Houston airport.

And as I stood in line in the cavernous, dreary, understaffed, customs station,

and I looked around at my own people—stressed-out, short-tempered, homesick

Americans--it struck me as clear as a bell that the only difference between this

place and Nicaragua was a few dollars, and they wouldn’t last forever. In fact, that wave had already crested. And I realized that if I wanted to help

people, and develop and strengthen communities, and build the foundations of a

just and sustainable society, the most important place in the world for me to do

that work was right here in the good, old US of A.

In the 10th Chapter of

Acts, Peter tells Cornelius, the Roman Centurion, that Jesus is Lord of All, by

which he means Lord of all peoples. But

he might as well have meant Lord of all times, all circumstances and

situations. As the exalted Son of God,

Jesus is Lord of the Universe; and as the man who died on the cross, he is the servant

of every particular thing in it. He is

Lord of Nicaragua and Lord of Petaluma.

He is Lord of your house, and your office, and your spouse and children. He is Lord of your bank account, of your car,

and the highway you drive on. He is Lord

of your bedroom, and bathroom, and the dishes in your kitchen sink. He is Lord of your dreams and of your fears,

of your proudest achievements, and your devastating losses. And as many times as you forget him, or

discount him, or betray him, he calls you back to begin again, a little

humbler, maybe, a little wiser, to find his place in your life, and yours in

his.

When you leave here today, maybe humming one

of those catchy Easter hymn tunes, and the flowers are blooming, and the hills

are still green, and the color and the fragrance of spring are everywhere, everything

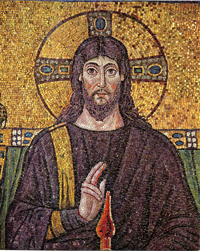

you see will be a sign of his resurrection.

Everyone you meet will be his glorious image. Nothing that happens to you, now or in the future,

will be able to put him back in his grave, or remove his name from your lips or

his word from your heart. Or so I’ve

been told. And today I could almost

believe it.