In

1994 I was in Berlin, and one day during my visit, I took a commuter train

north of the city to a suburb called Oranienburg. There I got off, and walked a few blocks from

the train station to a place known as Sachsenhausen. What I found there was field of symbols,

representing conflicting stories about what happened there, and why.

The

first such symbol meets the visitor at the entrance to the place, an imposing

two-story guardhouse with an arched entryway underneath in which there is a

wrought-iron gate. And worked into the

structure of the gate itself are bars that spell out the notorious motto of the

Nazi concentration camps—Arbeit macht

frei—which means, “Work makes you free.” It is a note of historical interest that

one of the notable forms of “work” to which the slave laborers of Sachsenhausen

were put was the manufacture on a massive scale of counterfeit foreign

currencies—English pounds, Swiss francs, American dollars.

And

this single fact encapsulates, in a way, the whole world of the camp, and of

the Nazi state of which it, and other camps like it, were the quintessential

expression. It was a counterfeit social

order, in which people were punished and killed for that which was no crime, in

which the “work” which supposedly made them “free” had no productive or

beneficial purpose, in which the whole system, which was supposed to be saving

civilization from barbarity and chaos was in fact a vast and barbaric criminal

enterprise.

We

can see this now with no difficulty at all, having the 20-20 vision of

hindsight. The Nazi system and its

demonic ideology is long vanquished, reduced to rubble, and so is the

counterfeit worker’s paradise that took its place. In the center of Sachsenhausen a massive

granite column built during the Communist East German period. It is both a memorial to the thousands of

leftist political prisoners and Russian prisoners of war who died there, and a monument

of victory, celebrating the Russian army that liberated the camp and crushed Fascism. And next to the column, almost as a wry

aside, was a newly-installed interpretive sign noting that Sachsenhausen

remained in operation for another decade after 1945, as a place of internment

for former Nazis and other enemies of the new, Communist state.

That

sign was itself a symbol of victory, a claim to have woken from the nightmare

of the past, in the clear day of a new liberal and democratic Germany, where

the truth about Sachsenhausen could now be told. It is a reunited Germany at the center of a pluralistic

Europe, that has moved beyond the nationalistic and ideological conflicts of

her history into political, cultural, and economic integration. And this Europe is a linchpin of new global

order of unprecedented productivity, opportunity, and prosperity, where work

really does make you free. Of course, more

than twenty years after 1994, it is less clear than it was how lasting that order

will be. And it remains to be seen what

irony people a century from now will find in the symbols it produced to

demonstrate its goodness.

But

in the meantime, people were making the most of that open space to transform

the symbolic landscape of Sachsenhausen.

I saw this in the camp’s “infirmary,” where doctors trained to comfort

and heal practiced a counterfeit of medicine, torturing living human subjects

in the name of scientific experimentation.

I happened to visit that place at just the same time as a group of

pilgrims from Israel was laying wreaths of fresh flowers on the operating

tables and saying prayers for those who suffered there. And in another place, on the outer wall of

the camp, there was a memorial to the members of the thriving gay subculture of

Berlin who were rounded up en masse and

died in Sachsenhausen. It was in the form

of a giant pink triangle, the badge, analogous to the yellow star for Jews,

that Nazi laws forced homosexuals to wear.

In

this way, persecuted groups have turned symbols of horror into defiant signs of

life. They say we will not accept your

attempt to erase the ones we love from the face of the earth. It is too late to save their lives, but it is

still possible to preserve their memories.

We may not know their names, but we know that they lived, and we know

how they died. We remember, and even

honor, the instruments of shame and death that were applied to them, as symbols

of our refusal to hide the truth that these were human beings, whose torture

and murder no rationalization could ever justify.

The

cross is just this kind of symbol. For

many centuries of the history of Christian art, the cross was a prevalent

symbol, but until the later Middle Ages it was rarely, if ever, a

crucifix. That is to say, it did not

depict a dead or dying man hanging on it.

This was because the cross is more than a memorial to the death of one

person. It had a more universal meaning,

as a reminder that the imperial system of Rome, that was supposed to bring law

and order, progress and enlightenment to its subject peoples, was a brutal

counterfeit that relied on the terror of the cross to keep its slaves in

line.

It

was a reminder that the Romans had their collaborators in putting Jesus to

death, the Jewish elite who decreed that it would better for an innocent man to

die in a travesty of justice, than to allow his imagination of the kingdom of

heaven to stir the common people up to challenge their subjugation. It is a symbol of all our human pretensions

to decide for ourselves who is in possession of goodness and truth and who is a

threat to these, to decide who is fit to live and command, and who is condemned

to slave and to die.

And

it is a revelation of the humanity of the victims that such pretensions

inevitably make. The cross is a symbol

of the witness that these victims bear.

When we remember the martyrs, we remember human beings whom systematic

violence tried to erase, whose example of true humanity shines out all the more

for being engulfed by darkness and falsehood.

We recount the gruesome details of their deaths because we wish to honor

their courage, and the price they paid for standing firm in the truth. Without memory of the manner in which they

gave their lives, the truth for which they laid them down is in danger of being

lost, and without that truth how can there be compassion, forgiveness, or restitution?

But

the cross is not only the sign of those who died heroically in the cause of

truth, whose names we hold in honor. It

stands for hope of remembrance, and thus of compassion, restitution, and

forgiveness for all the countless victims of murderous violence whose names are

unknown, who died for no good cause, and with no particular nobility or

courage. And such hope could only be

hope in God.

That

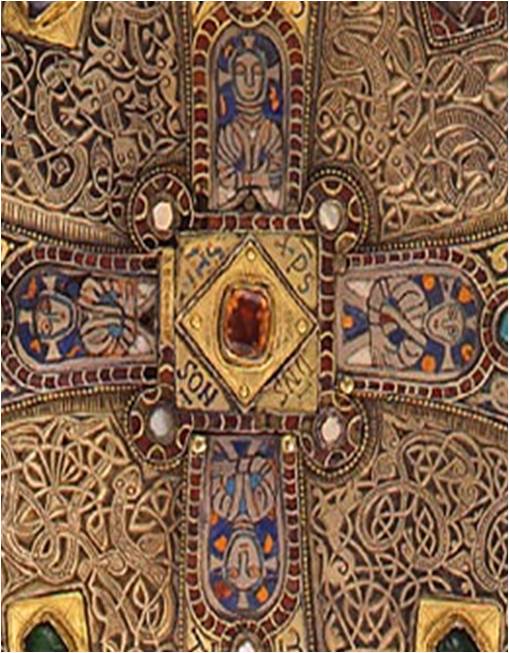

is why the earliest crosses in Christian art, and countless crosses throughout

the centuries down to the present day make no attempt to present a historically

accurate representation of the cross on which Jesus died. They are geometrical forms, often highly

stylized and adorned. Because the cross

is not simply a memorial to the suffering and death of Jesus; and it is not

only a disclosure of the falsehood of every rationale for terror, violence, and

murder; it is first and foremost a revelation of the glory of God. The cross is a sign of God who is life, whose

love of life reached into our world of death in the person of Jesus.

That

is why the earliest crosses in Christian art, and countless crosses throughout

the centuries down to the present day make no attempt to present a historically

accurate representation of the cross on which Jesus died. They are geometrical forms, often highly

stylized and adorned. Because the cross

is not simply a memorial to the suffering and death of Jesus; and it is not

only a disclosure of the falsehood of every rationale for terror, violence, and

murder; it is first and foremost a revelation of the glory of God. The cross is a sign of God who is life, whose

love of life reached into our world of death in the person of Jesus.

Because

he gave himself to the cause of life, the life that is the free gift of a

loving God to all creatures, the forces of death gathered around Jesus. Because he spoke the truth about the mercy of

God, that is for the unjust as well as the just, for sinners as well as the

righteous, for the poor and persecuted and afflicted as well as the proud and

powerful and prosperous, they showed him no mercy. But Jesus did not turn away from the end that

meets all human life in a world enslaved to death. He accepted its sentence, and suffered and

died like all its other victims. Yet he

died without submitting to the power of death, without succumbing to fear or self-pity,

or crying out for vengeance. He completed on the cross the work of his

life, of giving glory to God who is love that is unfazed by hate and life that

has no traffic whatsoever with death. And so his cross became our enduring symbol--of

what death is not, and of who God really is.

No comments:

Post a Comment