There was a lot I didn’t know when I went to the Rector

of my old church of

St. Gregory’s in San Francisco and told

him I thought, maybe, I was called to be a priest. I didn’t know much about the Bible, or the

history of the church, or how it was organized, and

what the life of a minister was really like.

I certainly didn’t know anything about the ordination process, and if I

had, I might never have had the courage to start. Because the truth is I was afraid to tell my

secret even to my friend the Rector—this secret I’d been

keeping even from myself. I was afraid

of what he might say, and how I might feel.

I was afraid I was mistaken, and afraid that I was not. Most of all I was

afraid to be seen.

And the process of becoming a priest

requires that you be willing to be seen.

You go through all these formal interviews with the parish Discernment Committee

and the Diocesan Commission on Ministry, and the Standing Committee and the Bishop.

You get evaluated by a psychologist. Each time you meet with these people you’re

trying to articulate your vision of yourself as a priest, but it’s extremely

awkward because all the while you’re wondering if it’s

real, and you know that they are, too. Because the way

we understand the call

to ordination in the Episcopal Church is

that my own internal sense of being called is not enough. Other people have to see it, too.

I had a friend at St. Gregory’s who chaired the committee

of lay people in the parish that met with me over a year or more to talk with

me about that

call, and hosted the meetings at her home. And I’ll never forget the time, after I’d

preached maybe my third or fourth Sunday sermon, when she came up to me and said,

“This time I saw that you could be my priest.” I could not

have made it through in the ordination process or my subsequent years of life as

a priest without moments like that one, when someone else could see what I had

lost sight of, or doubted was anything more than a mirage.

You can see something like this in

the story of the call of Samuel. Samuel is serving as a kind of apprentice to a priest named Eli in the temple at Shiloh, and one night The Lord calls to Samuel as he is lying

down to sleep, and the boy runs to Eli to see what he wants. The priest

tells him to go back to bed, because he had not called him. And the call comes a second time, and again

Samuel runs to Eli, and again Eli tells Samuel that he had not called. But when it happens a third time, Eli has the

wisdom to see what was going on, and he tells Samuel

that it is the Lord who is

calling. Samuel was called to be a

prophet, but to set out on his path he needed Eli to see him and recognize the

calling for what it was.

I believe that all of us need to

be seen in order to find our calling. It

is as true for teachers and scientists, nurses and bankers, artists and farmers,

as it is for prophets and priests. It’s

true of professions, but it’s just as true of other, more personal callings, as

parents and spouses and friends. Because no matter who we are—what kind of family we have,

or work we do, no matter what our talents, or disadvantages, or aspirations

might be—we do not earn our lives by our efforts, or take them by cunning or by

force. We receive them as a gift.

There is a voice calling out to each of us to accept the

gift of our own true life. There is a

vision in the mind of God of who each one of us is, and of who we are

becoming. That is why it is such a

blessing to meet someone who can speak to us with that voice, who

is able to see that vision. A

person like that gives us faith in the gift of ourselves—the power to embrace

it, and come fully alive.

The stories in the Gospels about Jesus’ calling his

disciples only make sense when you understand that he was that kind of

person. It seems unbelievable that Nathaniel’s

skepticism (“can anything good come out of Nazareth”) should change so

dramatically to whole-hearted belief, unless you imagine this kind of

experience of being seen. When Jesus says to Nathanael “I saw you under the fig tree” I don’t think the point

is that he is clairvoyant. That wouldn’t be enough to make Nathaniel

call him “Rabbi, Son of God, King of Israel.” To me, it’s the fig tree that’s

the key.

Because under the fig tree is not just someplace Nathaniel happened to be hanging out before Philip came

to tell him about Jesus. This is a

passage that is dense with references to the Hebrew scriptures, and in those

scriptures “under the fig tree” is the place of

freedom, fulfillment, and peace. The

classic text would be the book of Micah, Chapter 4:

they

shall beat their swords into ploughshares,

and their spears into pruning-hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more;

but they shall all sit under their own vines and under their own fig trees,

and no one shall make them afraid.

and their spears into pruning-hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more;

but they shall all sit under their own vines and under their own fig trees,

and no one shall make them afraid.

And

I think Nathanael’s fig tree takes us even deeper into the heart of the

scriptures, all the way back to the Garden

and the fruit of the forbidden tree, to a moment of seeing and being seen:

Then

the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they

sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves.

What blows Nathaniel’s mind is

that Jesus reminds him of a moment under the fig tree, a moment of being seen

naked, of knowing the presence of an other with whom there can be no pretense or

deceit, one who knows him as he really is; one who, at the same time, frees him

from fear, makes him self-sufficient and at peace. When Nathanael meets Jesus, he remembers that

moment, and his eyes are opened to recognize the one who saw him there.

Becoming a disciple of Jesus,

this story seems to say, happens when we see him as the one who sees us, as we

really are. And, as I said, the person

who can do that has given us the gift of our lives. But in the story Jesus also promises

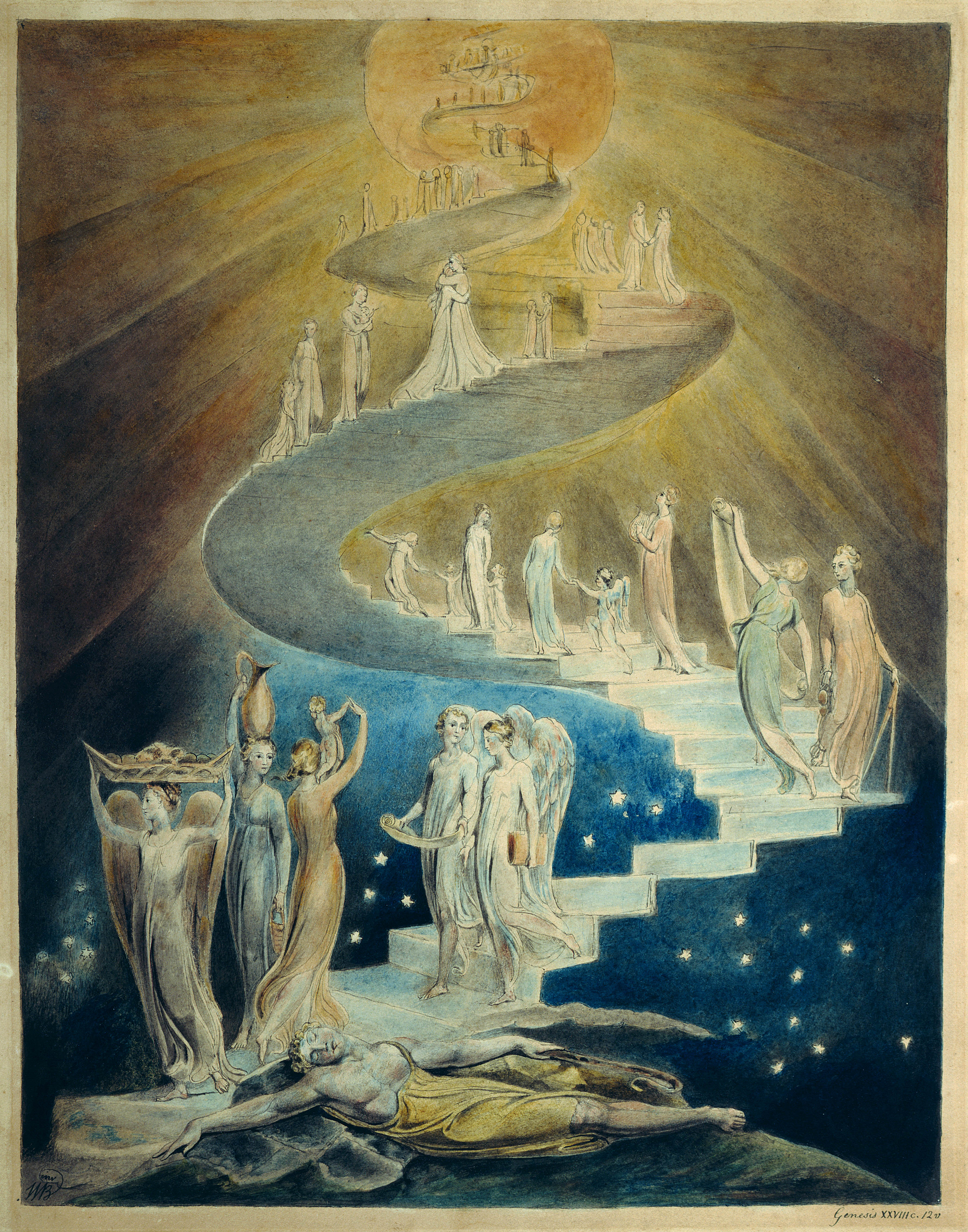

Nathanael that he will see something even greater. He makes one more reference to the Hebrew

Bible, to the legend of Jacob’s who fell asleep on a journey and dreamed of a

ladder on the earth reaching to heaven and angels coming and going on it. And he woke up and said, “Surely the Lord is in this place and I did not know

it. How awesome is this place! This is the gate of heaven.” And he set up an altar there and called it

Bethel, the house of God.

The call to follow Jesus starts

out innocuously enough—someone says “come and see.” And if we go and see, we soon find out that

we are being seen. We see that we are

naked, with nothing on but some fig leaves.

But we also start to see a vision of the person we are truly called to

be, who we are when we are not afraid, when we want for nothing, but are at

peace. We begin to recognize the one who

sees that person more clearly than we do ourselves, and to trust his vision

more than our own.

As that trust grows in us, a light

of hope is kindled in our hearts, the hope of seeing something even greater. We begin to sense that we are standing on

holy ground. We begin to glimpse a

vision not only of ourselves but of the whole world as it is seen through the

eyes of Jesus. We begin to understand

that this very place is the house of God, and gate of heaven. And this vision, and this hope, gives us a

new calling, one that unites all our individual vocations in the calling of the

church. It has two, interdependent

parts. The first is worship. And the

second is to show the whole world where we really are.