I spent most of last Monday digging

up an old, leaky irrigation system in the front yard, and I brought a portable

radio outside with me, to listen to while I worked. After a couple of hours of informative

programming on a listener-sponsored community station, I decided I’d had enough

of that for the day and turned to one of my guilty pleasures—sports talk

radio. And in that world the news was

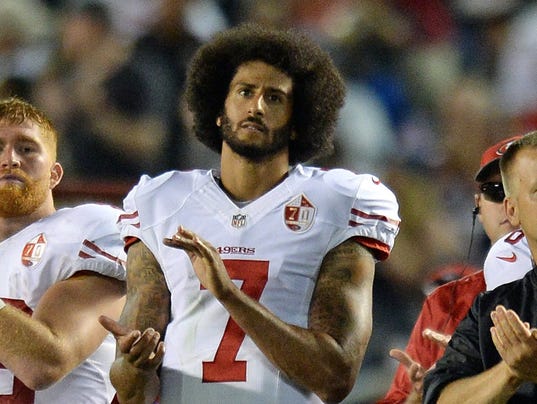

all about a quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers named Colin Kaepernick, who

has been remaining seated during the national anthem before the team’s

pre-season football games. The first time

he did it, no one noticed, but at last Sunday’s game in Green Bay, Wisconsin, a

reporter saw him, and asked him about it in a locker-room interview after the

game, at which point Kaepernick declared that he was sitting in protest of the

oppression of African-Americans and other people of color in the United

States.

The hosts of my radio talk show felt

compelled to weigh in with their opinions about what Kaepernick had done, and

then they opened the phone lines and took calls from listeners who expressed

their wide-ranging and contradictory views.

As the week went on, this controversy spread across the media landscape,

with everyone from Kaepernick’s former coach, Jim Harbaugh, and 49ers legend

Jerry Rice, to the Republican Party’s nominee for President publicly expressing

their disapproval. Meanwhile, some

current and former members of the armed services, not wanting to let others took

offense on their behalf, “tweeted” messages of support at #VeteransForKaepernick. At the 49ers final exhibition game on

Thursday, at “Salute to the Military Night” in San Diego, Kaepernick and

teammate Eric Reid knelt on one knee during the anthem, in what they intended

as a gesture of mingled defiance and respect, and tens of thousands of fans in

the stadium got to contribute their voices to the conversation by booing

Kaepernick lustily every time he was on the field.

Clearly, Colin Kaepernick has

touched a nerve by taking this stand, or rather, this seat or this knee. He has aroused countless people to want to have

their views be heard on what they think of his actions, and whether his taking

them is justified, whether he is personally qualified to be making this

protest, and whether the way he has gone about it is appropriate or offensive. And I personally am not immune to this

reaction. But I’m going to spare you my

opinions, because I think today’s scripture readings point us in a different

direction. They are asking us to think,

not about what Colin Kaepernick’s protest means to us or to others, but about what

it is actually like for Colin Kaepernick.

When all his teammates and coaches, and the owner of the team, and every

one of the fifty-thousand other people in the stadium who were physically able

to do so rise to their feet in a ritual of unity and love for our country, a

ritual you yourself have proudly participated in hundreds of times before in

your high school, college, and professional careers, what is it like to sit,

alone, on the bench?

Jesus says that this kind of loneliness,

this alienation from other people, is what we can expect when we join his

movement. We can expect to have moments

when we are estranged from the groups we thought we wanted to belong to, and

even from the person we thought we would be to be loved and accepted by them. It is an estrangement that can turn us into

enemies in the eyes of our nation, our church, even our family: "Whoever

comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers

and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple.” This is a hard

saying, and it’s natural to think, “Jesus can’t really mean that—he must be overstating

the case.” And in a sense he is, but the purpose of the exaggeration is to

underscore his essential point: that following him means sharing his commitment

to doing the will of God whatever the cost.

We have to be ready for those moments when we know what we must do to be

faithful to the truth of our lives, when even though it is certain we will be

misunderstood and hurt people we care about, and in those moments we have to be

willing to act.

If we’re lucky we are never called

to do this at the cost of our health, our freedom, or our lives. But the point is that we are never truly free

unless we give God the freedom to tell us what to do and how far to go. We are never fully alive if we are not

willing to lay our lives on the line in response to the Spirit’s stirring of our

conscience. And if we are fortunate

enough to live in a society where Christians are the majority, where social

deviance and political dissent are widely tolerated, it shouldn’t serve as an

excuse to take fewer risks with our freedom, or stands on our conscience, but

as a license to take more. This doesn’t

necessarily mean that we have to go out looking for courageous stands to take; the

naturally-unfolding circumstances of our lives give us ample opportunities to take

difficult and unpopular actions. Even

those actions we recognize as especially heroic often turn on a fairly straightforward

personal choice. Rosa Parks had no idea,

when she refused to give up her seat in 1955, that she would catalyze the

Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Civil Rights movement. She was simply, she would later say, “tired

of giving in.” Yet as this example shows

us, it is actions, even modest personal ones, that really count. They have far-reaching effects that words do

not.

Actions create stories, and symbols,

with the power to move other people. In

July LeBron James and three other professional basketball superstars stood

together and made speeches, at a nationally-televised awards ceremony, about racial

division, systemic failure, and violence both by and against the police. It received a polite murmur in response, whose

tone was generally appreciative. But those

speeches were a blip on the meter compared to the volume and intensity of the

reaction that Colin Kaepernick got, by sitting alone, saying nothing. His action transformed an obligatory ritual that

rarely gets a second thought, into a highly charged symbol of our country’s

congenital wound of racist oppression and violence, a wound that has never

healed, and continues to tear us apart.

And in the days since, as people have passionately argued with each

other about their interpretations of what he did, that disunity has been

visible for everyone to see. Whatever

you make of Kaepernick’s action, it is hard to dispute its effectiveness.

Of course, there is no greater

example of the power of an act to transform a symbol than the one given us in

the gospel. Jesus’ teachings about the

forgiveness of sins and the blessedness of the poor, about loving one’s

enemies, and the subversive, hidden nearness of the Kingdom of God, would surely

have been forgotten centuries ago if he had not been willing to die on a

cross. In doing so, Jesus changed that cross from a

sign of terror and despair at the ruthless power of the Roman state, into a

symbol of unconquerable freedom of conscience, and faithfulness to the will of

God. And God’s act of raising Christ

from the dead completed the transformation, so that now the cross is a symbol

of the truth of all that Jesus taught, of justice, forgiveness and

reconciliation, of abundant life’s victory over death, a sign of promise even

to those without a hope in the world, that their suffering itself is eloquent,

and God is listening.

And for those of us who have

something left to give the world, and come to Jesus to take up his cross, it is

the sign of our freedom and our mandate, in gestures of protest and works of

mercy, to act like him. The importance

of these actions is not measured in how much they shift the balance of political

power, or even lessen the suffering in the world. In those respects, they often seem to be so

much spitting in the wind. But they are also

important as signs of resistance and hope.

They create symbols and stories that inspire and provoke, encourage and

infuriate, chasten and embolden, others to act.

No comments:

Post a Comment