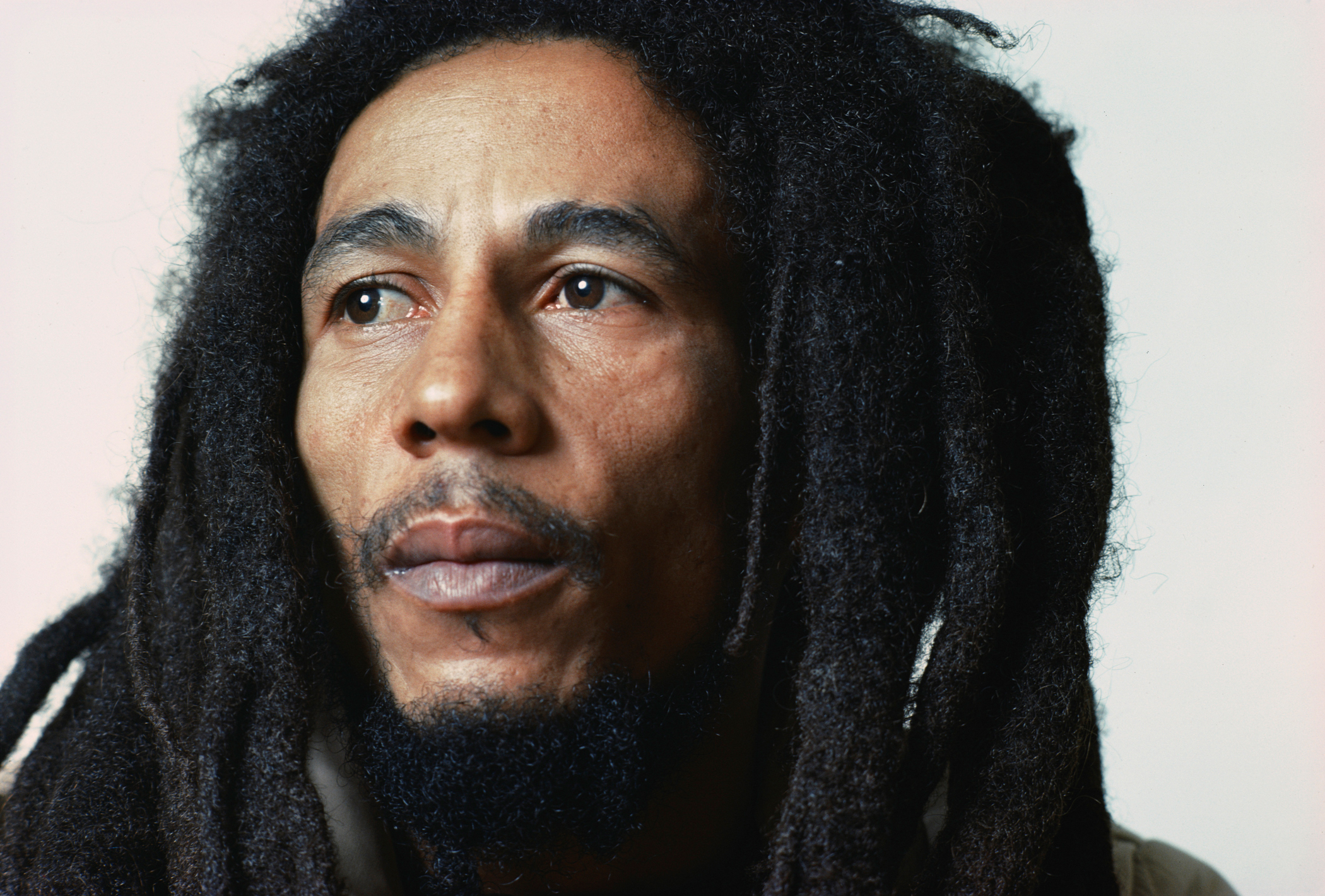

By the time I knew who Bob Marley

was, it was too late. Funny thing was, I

had my chance to see him. On November 4,

1979 he played two shows at Memorial Auditorium in Burlington, Vermont. You can buy an original poster for the

concerts for a thousand dollars on the internet. But at the time the tickets sold for

$7.50. I was a sophomore in High School,

not quite fourteen years old, and not yet in the habit of going to rock

concerts. And Bob Marley was not a rock

musician, exactly. He and his band, the

Wailers, played reggae, music from the urban slums of Kingston, the capital of Jamaica,

that fused American Soul, Gospel, and Rhythm and Blues, with traditional folk

music from the countryside with deep roots in African culture.

I read about that in the free

weekly paper, the Vermont Vanguard, which published an interview to promote the

concerts. It was the first I’d heard of

him, and I was intrigued. But I didn’t

drive yet, and neither did any of my friends; there was no bus out to where we

lived, 15 miles from Burlington, and the 4th of November was a school

night. So I didn’t go, but I might have

made more of an effort if I’d known then what I soon came to know. I didn’t know that Bob Marley was a legendary

live performer who was on his way to becoming a global superstar. I didn’t know that the following year my

brother Ben was going to go away to boarding school and come back for Christmas

a fan.

When I found out about that, I bought

Ben a cassette tape of the album Survival

and put it under the tree, but it turned out he already had it, and he gave

it back to me. I still remember putting

it into a little portable tape player one Saturday morning to listen to while I

did my weekly chores. It was unlike any

music I’d ever heard before, and I didn’t know what to make of it at first. But I kept listening, and pretty soon I was playing

it over and over again. It wasn’t long

after that I went over to my friend Fred’s house and discovered that his mother

had a bunch of Bob Marley and the Wailers records. So I rode my bike to Burlington the next

weekend, and bought a bunch of blank cassettes, and I taped every one of those

albums. Over the following months I spent

the money I earned mowing lawns at the record store, filling in the rest my

collection.

I might have made more of an effort

to get to the Bob Marley concert that night if I’d known he was about to die. I was on the staff of the high school newspaper

by then, and I wrote a heartfelt obituary and we published it, bordered in

black. The chance I’d missed, to see him

in person, would never come again. But

in the long run, his impact on my life wasn’t any less because of it. Unlike most of the music I was a fan of in

those days, I still listen to Bob Marley.

It makes me proud and happy that now my wife and daughter like him,

too. I guess that’s because the messages

that made his songs so meaningful to me when I was a teenager still matter to

me today—loving and giving thanks to God, brotherhood and sisterhood with all

human beings; outrage and sorrow at violence, injustice, and war; faith in the

power of truth to overcome greed and delusion; championing the right of the poor

to stand up and resist their oppressors; joyful celebration of love, culture,

community, and the basic goodness of life.

The Gospel of John doesn’t say

whether the Greeks who came to Jerusalem for the Passover ever got to see Jesus

in person. It seems like they

didn’t. And maybe in the short run, it

felt to them like a missed opportunity and a grave disappointment. But events were moving quickly for Jesus at

that time, according to a different agenda than the one those Greeks had in

mind. The time when they asked to see

him was exactly the moment for Jesus to begin the final movement of his destiny. The things that those Greeks were hoping to

get from him—new insight into the working of God in the world and in their

lives, a transforming experience of the power of truth and love to overcome

alienation and despair—these things were about to become available to them and to

everyone, in a new way that did not depend on being in his physical presence.

But in order for that to happen

Jesus had to die. Why that is, and how

that works, and what that means, are questions that never go away. They are involved with the questions about why

there is so much evil and suffering in the world, and what is the purpose of

human life, and why things never measure up to the potential we can see they

have. I think the church has sometimes

done a disservice with its overly tidy explanations for all of this, and how it

is that Jesus’ being “lifted up” on the cross speaks to the heart of the matter. We have held these questions at a safe

distance, for philosophical analysis and theological speculation, or we have smothered

them with pious sentimentality.

What is clear and indisputable is that

Greeks did embrace the Gospel of Jesus, by dozens, and then by hundreds, and

thousands, and hundreds of thousands.

And so did Romans and Syrians, Egyptians and Mesopotamians, Ethiopians

and Arabs, and Irish and Mexicans and Chinese. Why a religion that centers on the agonizing

public execution of its founder could spread across the world like this is another

puzzle that people like to try to solve.

They explain it in terms of social psychology and cultural anthropology,

comparative religion and politics. But maybe

the most satisfactory explanation is the simplest one—that people simply

recognize it as true.

The death of Jesus tells us

something true about this world we live in and about ourselves. It tears away the veil from the ruler of the

world, revealing the terror and violence behind the lofty propaganda, idolatrous

religion, and mockeries of peace and justice.

It shows us how we acquiesce to these manipulations, how we crave the

security of the herd, and love to be told that we are the ones who play by the

rules, and so we are the ones who deserve the rewards. It

shows us how the spirit that lays false claim to rule the world holds sway in our

own hearts, seeking to be admired and honored, seeing rivals and enemies

everywhere, loving to play the game of blame and shame, because the humiliation

of another is the best defense against our own.

The cross is this world’s moment of truth, and as much as we might want

to shrink from it, there is something in us that recognizes it for what it is.

This attracts us, because deep down

we long to be free. And the world’s

captivity to sin and death is only part of the truth that Jesus knew. The other side of the truth is that the world

is worth dying for. Because all

pretensions of the false ruler of the world aside, it is God’s creation. God, who is the only source of its life and

light, loves this world and means to save it.

The Gospels tell us that the Jesus understood this and gave himself

completely to the truth of it, letting the Spirit of healing, liberating, and

recreating the world be his guide in all things. It wasn’t like he wanted to be crucified, but

he knew what he was up against well enough to realize that that was where he

was headed. And he was willing to go, if

that was what it would take to show the world that only love and truth and

faith in God can save us.

Jesus tells the crowd that “now is

the judgment of this world” but that hour is always now. He is the seed that fell into the ground and

died, so that he would bear fruit in countless men and women like you and me. He is always lifted up before us, drawing us

to himself, calling us to see the true glory of the world, which is his path of

love and service. The choice is always ours.

In the immortal words of the great Robert

Nesta Marley,

“Could you be loved? Then be loved.”

No comments:

Post a Comment